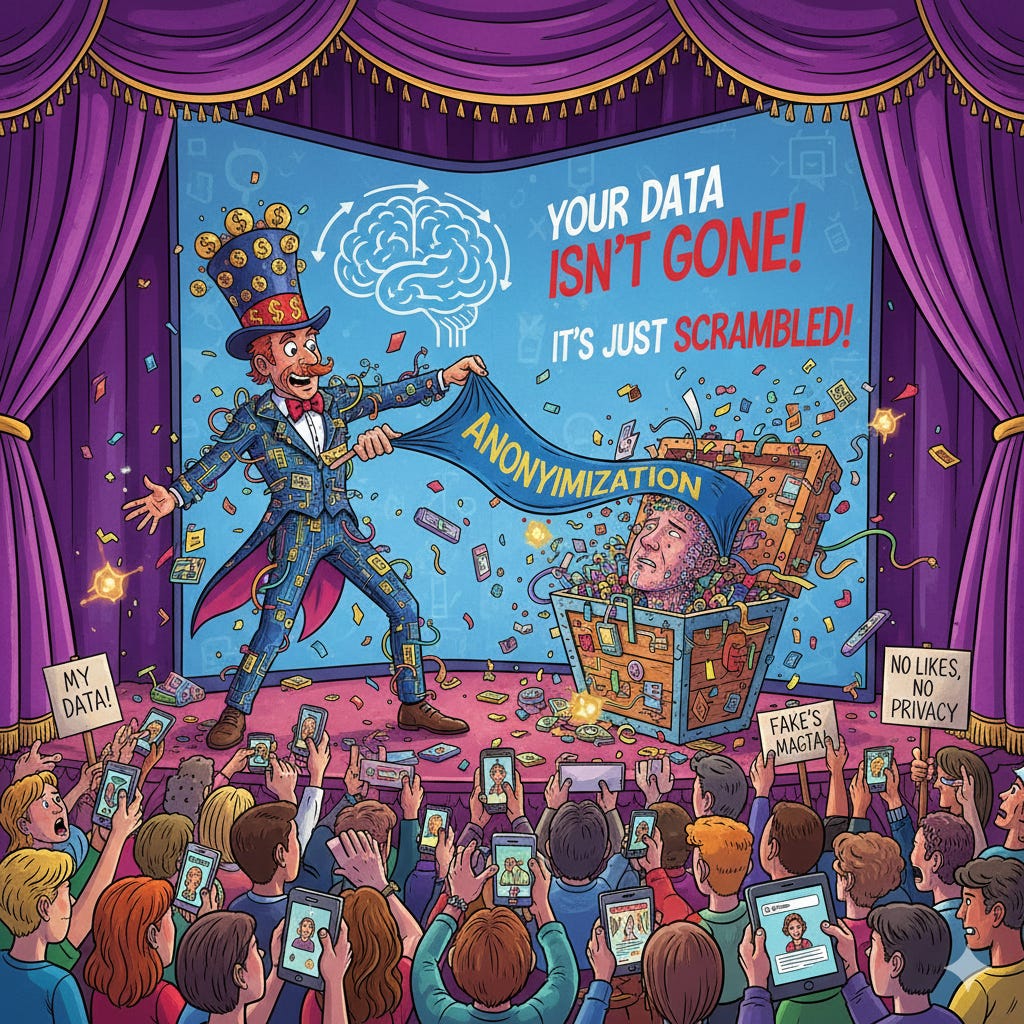

The Illusion of Anonymization: Why Your "Anonymous" Data Probably Isn't

In my point of view, the problem Isn’t technical. It’s the system.

In 2006, Netflix started a public contest: improve their movie suggestion system by 10%. To help, they released data from 500,000 subscribers. They removed names and ID numbers. It seemed safe.

However, researchers Arvind Narayanan and Vitaly Shmatikov proved it wasn’t. By matching the “anonymous” Netflix data with public reviews on IMDb, they identified users with a huge accuracy. Just a few known movie ratings were enough to reveal a person’s identity, political views, and private habits. This case became a famous example of why anonymization is hard.

I wrote about the Paul Neil case here, however, to mention, in 2007, Interpol released photos of Christopher Paul Neil, a man wanted for serious crimes against children. His face was hidden using a “swirl” effect, like a a circular distortion that looks impossible to fix. But forensic experts used computer math to reverse the swirl and reconstruct his original face. He was identified and arrested. The “visual anonymization” failed (thank god in this case).

Anonymization faces a major problem: data does not exist in a vacuum. In the early 2000s, Latanya Sweeney showed that just three pieces of information, birth date, gender, and zip code, can identify 87% of people in the U.S. Today, with so much data available online, this risk is even higher.

Common privacy techniques try to fix this by grouping records together so people look the same. But these methods assume you can control everything. In the real world, data moves through complex systems where control is an illusion.

In 2019, the New York Times revealed a case that showed a new side of the problem: a company called Clearview AI had collected more than 3 billion face images from the internet. They took these from social media, news sites, and public platforms to build a facial recognition system for the police.

Disturbing alerta: even old photos from completely different times could be matched instantly. A person photographed at a protest years ago, or at a graduation party, could be identified in seconds using a new photo from any situation.

The speed and scale of this made old debates about “public data” versus “grouped data” outdated. Clearview proved that, in the age of AI, there is no such thing as a truly anonymous photo on the internet. Every image is potentially a permanent biometric ID, just waiting for the right algorithm to find a match. This case forced regulators around the world to completely rethink how they handle biometric data and visual privacy.

But the real challenge is, for me, the Invisible chain of vendors.

Think about a common situation: you receive ID documents for a security check. Your company doesn’t process them internally, so you send them to a specialized vendor. That vendor stores the files on a cloud server like AWS. That server company might use Google’s AI to read the data.

In one single step, the document passed through five different organizations. Now, here is the big question: if the person asks you to delete their data, can you guarantee it is removed or made anonymous across that entire chain?

The honest answer is almost always “no.” Most companies use hundreds of connected software services. Making sure data is truly anonymous across all these layers is nearly impossible without perfect oversight.

Because old methods fail, “differential privacy” has become a stronger option. It adds mathematical “noise” to the data. This ensures that adding or removing one person’s info doesn’t change the overall results. The U.S. Census Bureau, Google, and Apple already use this. It uses a setting called “epsilon” to balance privacy and accuracy. A lower epsilon means more privacy but less precise data. It is a solid, mathematical solution, but it is hard to set up and doesn’t work for every business… I mean, if you are not a huge company data, probably it will never be a reality for you.

Well, for tech leaders and privacy experts, the advice I get for you is: if you cannot prove mathematically that data is anonymous, treat it as personal data. This isn’t being negative, it’s being accurate my dear.

Anonymization isn’t “on or off.” It is a constant process of managing risk. You must look at the context: how much data do you have? How sensitive is it? Could it be linked to other sources?

The Netflix and Christopher Paul Neil cases are symptoms of a hard truth: in a world where everything is connected, true anonymity is very difficult.

When you add long chains of vendors, the challenge gets even harder.

The solution to the problem of cascading anonymization requires a basic change in thinking: adopting a “zero trust“ architecture for personal data. This means using a model where every connection with a vendor follows three strict rules.

First, minimize data at the start: Never send personal data to outside vendors if it isn’t absolutely necessary. It is better to use tokens or “fake” IDs that only your controlled system can turn back into real data.

Second, complete tracking: Keep a permanent record (like an audit log or blockchain) of every system that touched the data. This record should show the time, the reason, and a digital confirmation that the data was deleted.

Third, strict contracts with tech proof: Require vendors to use automated tools (like APIs or webhooks) that confirm data deletion in real-time. Do not rely only on a promise in a contract.

Companies like Apple have shown it is possible to process sensitive info through “secure enclaves.” In these secure digital zones, even the vendor cannot see the actual data. For smaller companies, the best way is to limit the number of outside partners and only work with a few certified vendors who are regularly checked.

Cascading anonymization is not impossible! but it requires a planned architecture, not just a reaction to problems.

The solution is strong management, building privacy into the system from day one, and keeping clear records of technical decisions. Investing in these processes isn’t just about following laws, it’s about business integrity and respecting human rights.