🕊️ Erase my name, Amen: The right to be forgotten, even by God

When the GDPR knocks on the sacristy door, to whom should we plead for mercy?

When I started this newsletter, I thought: I won’t be controversial, so no talking about football, religion, or politics.

In the last post, I talked about politics, and now I’m talking about religion. If my team loses this weekend, I’ll talk about football too. (just kidding)

In the name of the Father

Baptism, they say, is a rite of passage. For some, it’s also an eternal entry in the Church’s official records (almost like a sacred blockchain) and, more recently, in a database, since churches are modernizing too, right?

But here's the thing: a bunch of former Catholics have decided they want those records deleted, and they’re using data privacy laws to make it happen.

“Don’t call me a believer anymore, call me a data subject exercising my right to be forgotten.”

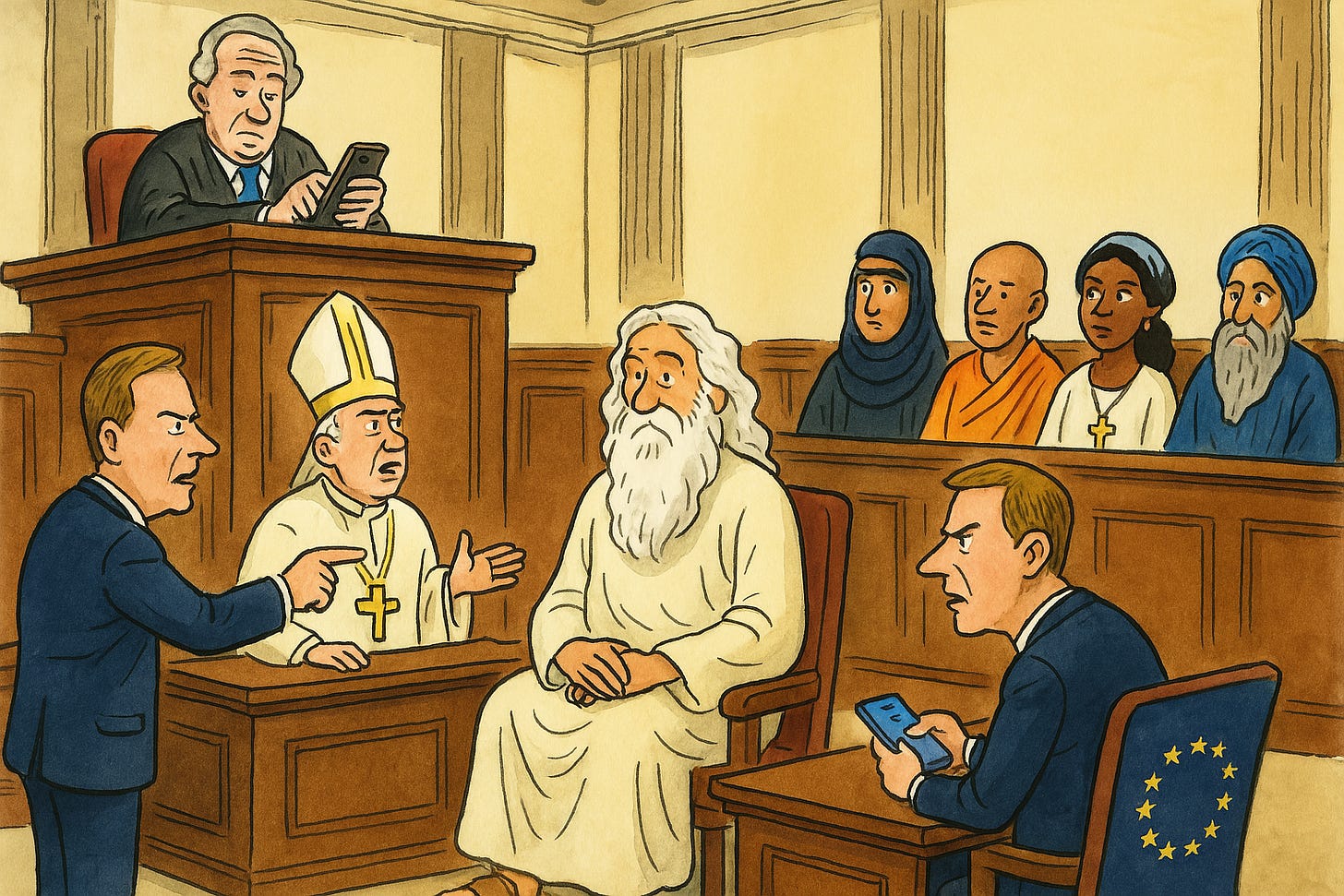

Well, the case made its way to the Court of Justice of the European Union, and the trial has all the ingredients for controversy: privacy, religion, and a challenge to the status quo. That’s why I created the image for this post (courtesy of GPT, of course, I haven’t become a cartoonist).

If you think all this is nonsense, hear me out. We’re talking about sensitive data (or special category data), the kind the GDPR treats with almost maternal care. Article 9 of the European regulation is clear: information revealing religious beliefs can only be processed under very specific conditions. But then the Church steps in and says, well, hold on! this isn’t really personal data, it’s historical heritage.

Of the Son

The question the European court is trying to answer is this: can someone who was baptized at six months old (without even being able to hold up their own head), now, as a grown-up taxpayer, request the deletion of that record?

In Ireland, a citizen spent six years fighting this battle. 1The Data Protection Commission ruled that the Church could retain the data based on “legitimate interest.”

A footnote in the sky?

Summary of the IN-19-7-6 case2

The Archbishop can lawfully rely on legitimate interests under Article 6(1)(f) of the GDPR as a legal basis for processing the personal data of individuals whose information is recorded in the Baptism Register, even when those individuals no longer wish to be associated with the Catholic Church

As long as safeguards are in place, the Archbishop’s interest in keeping the personal data in the Baptism Registers is not outweighed by the interests or fundamental rights and freedoms of the data subjects

Individuals who no longer consider themselves members of the Catholic Church do not have the right to have their personal data deleted from the Baptism Registers under Article 17(1)(a)-(f) of the GDPR

When a data subject no longer wishes to be a member of the Catholic Church, the Archbishop may add a supplementary note in the baptism record stating: “No longer wishes to be identified as Roman Catholic”

In other words, under this decision, the Church can keep the baptism record but must add a note to the person’s entry indicating that they no longer wish to be identified as Catholic.

The Church might still think you’re one of them, but at least your row in the sacred Excel sheet now comes with a footnote.

This is largely because the GDPR itself includes exceptions for processing by religious institutions, as long as the data is processed only within the context of the organization and not shared with third parties.

Of the Holy Spirit

So far, fair enough. But when someone says they no longer belong to that faith, doesn’t it make logical sense to stop processing that data? Brazil’s LGPD, for all its regulatory gaps, at least makes it clear that processing sensitive data requires explicit consent. And in my view, if you don’t want to be on the divine spreadsheet anymore, deletion should be the default.

The questions now being raised at the altar are:

1 – Should Article 17(1) of Regulation (EU) 2016/679, read together with the right to data protection as guaranteed by Article 8 of the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union (‘the Charter’), freedom of thought, conscience and religion under Article 10 of the Charter, Article 9 of the European Convention on Human Rights, and the principle of separation of Church and State as enshrined in Articles 19 and 21 of the Belgian Constitution, be interpreted to mean that a person baptized as a child who, as an adult, wishes to disassociate from the Roman Catholic Church, has the right to have their personal data deleted from the baptismal register?

2 – In this context, does it make any difference, under Article 17(1)(c) of the GDPR, that according to the controller, the baptism record affects the fundamental rights (freedom of religion) of the controller himself and the Catholic Church community he represents?

3 – Does it matter that the baptism register is not digital, but a single physical book with double-sided pages that also include personal data of other individuals?

4 – Does it matter that the book itself is considered a historical artifact and that the baptism entry is a unique historical record with no backup elsewhere, and that the data is also being processed for purposes of archiving in the public interest, scientific or historical research, or statistical purposes under Article 17(3)(d) of the GDPR?

5 – If there is indeed a right to erasure under Article 17(1), and if no exception under Article 17(3) applies, would that right to erasure be considered fulfilled, by analogy, if a note is added to the baptismal register stating that the person has left the Church?

If all this sounds surreal, welcome to the brave new world of data protection. Leaving a religion is now an international legal case. And maybe that’s just how it has to be.

Amen.

https://www.irishlegal.com/articles/eu-court-to-consider-ex-catholics-right-to-baptismal-register-erasure

https://www.dataprotection.ie/en/dpc-guidance/law/decisions-made-under-data-protection-act-2018/Inquiry-into-processing-of-Church-Records-by-the-Archbishop-of-Dublin-the%20Archbishop